MTOR

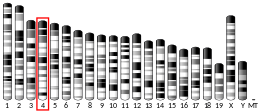

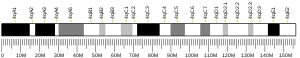

Sisarski cilj za rapamicin (mTOR),[5] znan i kao mehanistički cilj rapamicina, a ponekad i kao FK506-vezujući protein 12-rapamicinu pridruženi protein 1 (FRAP1), jest kinaza koji je kod ljudi kodiran genom MTOR sa hromosoma 1.[6][7] mTOR je član porodice protein-kinaza, fosfatidilinozitol 3-kinaza-vezane kinaze.[8]

mTOR se povezuje sa drugim proteinima i služi kao osnovna komponenta dva različita proteinska kompleksa, mTOR kompleksa 1 i mTOR kompleksa 2, koji regulišu različite ćelijske procese. Konkretno, kao ključna komponenta oba kompleksa, mTOR funkcionira kao serin/treonin protein-kinaza koja regulira ćelijski rast, proliferaciju ćelija, ćelijski motilitet, preživljavanje ćelije, sintezu proteina, autofagiju i transkripciju.[9][10] Kao jezgarna komponenta mTORC2, mTOR također funkcionira kao tirozin protein-kinaza koja promovira aktivaciju insulinskih receptora i insulinolikog receptora faktora rasta 1.[11] mTORC2 je također uključen u kontrolu i održavanje aktinskog citoskeleta.[9][12]

Aminokiselinska sekvenca

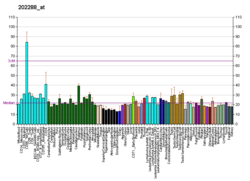

[uredi | uredi izvor]Dužina polipeptidnog lanca je 2.549 aminokiselina, a molekulska težina 288.892 Da.[11]

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLGTGPAAAT | TAATTSSNVS | VLQQFASGLK | SRNEETRAKA | AKELQHYVTM | ||||

| ELREMSQEES | TRFYDQLNHH | IFELVSSSDA | NERKGGILAI | ASLIGVEGGN | ||||

| ATRIGRFANY | LRNLLPSNDP | VVMEMASKAI | GRLAMAGDTF | TAEYVEFEVK | ||||

| RALEWLGADR | NEGRRHAAVL | VLRELAISVP | TFFFQQVQPF | FDNIFVAVWD | ||||

| PKQAIREGAV | AALRACLILT | TQREPKEMQK | PQWYRHTFEE | AEKGFDETLA | ||||

| KEKGMNRDDR | IHGALLILNE | LVRISSMEGE | RLREEMEEIT | QQQLVHDKYC | ||||

| KDLMGFGTKP | RHITPFTSFQ | AVQPQQSNAL | VGLLGYSSHQ | GLMGFGTSPS | ||||

| PAKSTLVESR | CCRDLMEEKF | DQVCQWVLKC | RNSKNSLIQM | TILNLLPRLA | ||||

| AFRPSAFTDT | QYLQDTMNHV | LSCVKKEKER | TAAFQALGLL | SVAVRSEFKV | ||||

| YLPRVLDIIR | AALPPKDFAH | KRQKAMQVDA | TVFTCISMLA | RAMGPGIQQD | ||||

| IKELLEPMLA | VGLSPALTAV | LYDLSRQIPQ | LKKDIQDGLL | KMLSLVLMHK | ||||

| PLRHPGMPKG | LAHQLASPGL | TTLPEASDVG | SITLALRTLG | SFEFEGHSLT | ||||

| QFVRHCADHF | LNSEHKEIRM | EAARTCSRLL | TPSIHLISGH | AHVVSQTAVQ | ||||

| VVADVLSKLL | VVGITDPDPD | IRYCVLASLD | ERFDAHLAQA | ENLQALFVAL | ||||

| NDQVFEIREL | AICTVGRLSS | MNPAFVMPFL | RKMLIQILTE | LEHSGIGRIK | ||||

| EQSARMLGHL | VSNAPRLIRP | YMEPILKALI | LKLKDPDPDP | NPGVINNVLA | ||||

| TIGELAQVSG | LEMRKWVDEL | FIIIMDMLQD | SSLLAKRQVA | LWTLGQLVAS | ||||

| TGYVVEPYRK | YPTLLEVLLN | FLKTEQNQGT | RREAIRVLGL | LGALDPYKHK | ||||

| VNIGMIDQSR | DASAVSLSES | KSSQDSSDYS | TSEMLVNMGN | LPLDEFYPAV | ||||

| SMVALMRIFR | DQSLSHHHTM | VVQAITFIFK | SLGLKCVQFL | PQVMPTFLNV | ||||

| IRVCDGAIRE | FLFQQLGMLV | SFVKSHIRPY | MDEIVTLMRE | FWVMNTSIQS | ||||

| TIILLIEQIV | VALGGEFKLY | LPQLIPHMLR | VFMHDNSPGR | IVSIKLLAAI | ||||

| QLFGANLDDY | LHLLLPPIVK | LFDAPEAPLP | SRKAALETVD | RLTESLDFTD | ||||

| YASRIIHPIV | RTLDQSPELR | STAMDTLSSL | VFQLGKKYQI | FIPMVNKVLV | ||||

| RHRINHQRYD | VLICRIVKGY | TLADEEEDPL | IYQHRMLRSG | QGDALASGPV | ||||

| ETGPMKKLHV | STINLQKAWG | AARRVSKDDW | LEWLRRLSLE | LLKDSSSPSL | ||||

| RSCWALAQAY | NPMARDLFNA | AFVSCWSELN | EDQQDELIRS | IELALTSQDI | ||||

| AEVTQTLLNL | AEFMEHSDKG | PLPLRDDNGI | VLLGERAAKC | RAYAKALHYK | ||||

| ELEFQKGPTP | AILESLISIN | NKLQQPEAAA | GVLEYAMKHF | GELEIQATWY | ||||

| EKLHEWEDAL | VAYDKKMDTN | KDDPELMLGR | MRCLEALGEW | GQLHQQCCEK | ||||

| WTLVNDETQA | KMARMAAAAA | WGLGQWDSME | EYTCMIPRDT | HDGAFYRAVL | ||||

| ALHQDLFSLA | QQCIDKARDL | LDAELTAMAG | ESYSRAYGAM | VSCHMLSELE | ||||

| EVIQYKLVPE | RREIIRQIWW | ERLQGCQRIV | EDWQKILMVR | SLVVSPHEDM | ||||

| RTWLKYASLC | GKSGRLALAH | KTLVLLLGVD | PSRQLDHPLP | TVHPQVTYAY | ||||

| MKNMWKSARK | IDAFQHMQHF | VQTMQQQAQH | AIATEDQQHK | QELHKLMARC | ||||

| FLKLGEWQLN | LQGINESTIP | KVLQYYSAAT | EHDRSWYKAW | HAWAVMNFEA | ||||

| VLHYKHQNQA | RDEKKKLRHA | SGANITNATT | AATTAATATT | TASTEGSNSE | ||||

| SEAESTENSP | TPSPLQKKVT | EDLSKTLLMY | TVPAVQGFFR | SISLSRGNNL | ||||

| QDTLRVLTLW | FDYGHWPDVN | EALVEGVKAI | QIDTWLQVIP | QLIARIDTPR | ||||

| PLVGRLIHQL | LTDIGRYHPQ | ALIYPLTVAS | KSTTTARHNA | ANKILKNMCE | ||||

| HSNTLVQQAM | MVSEELIRVA | ILWHEMWHEG | LEEASRLYFG | ERNVKGMFEV | ||||

| LEPLHAMMER | GPQTLKETSF | NQAYGRDLME | AQEWCRKYMK | SGNVKDLTQA | ||||

| WDLYYHVFRR | ISKQLPQLTS | LELQYVSPKL | LMCRDLELAV | PGTYDPNQPI | ||||

| IRIQSIAPSL | QVITSKQRPR | KLTLMGSNGH | EFVFLLKGHE | DLRQDERVMQ | ||||

| LFGLVNTLLA | NDPTSLRKNL | SIQRYAVIPL | STNSGLIGWV | PHCDTLHALI | ||||

| RDYREKKKIL | LNIEHRIMLR | MAPDYDHLTL | MQKVEVFEHA | VNNTAGDDLA | ||||

| KLLWLKSPSS | EVWFDRRTNY | TRSLAVMSMV | GYILGLGDRH | PSNLMLDRLS | ||||

| GKILHIDFGD | CFEVAMTREK | FPEKIPFRLT | RMLTNAMEVT | GLDGNYRITC | ||||

| HTVMEVLREH | KDSVMAVLEA | FVYDPLLNWR | LMDTNTKGNK | RSRTRTDSYS | ||||

| AGQSVEILDG | VELGEPAHKK | TGTTVPESIH | SFIGDGLVKP | EALNKKAIQI | ||||

| INRVRDKLTG | RDFSHDDTLD | VPTQVELLIK | QATSHENLCQ | CYIGWCPFW |

Funkcija

[uredi | uredi izvor]mTOR integrira ulaz iz uzvodnih puteva||transdukcija signala|transdukcije signala]], uključujući insulin, faktore rasta (kao što su IGF-1 i IGF-2), i [ [aminokiselina]].[10] mTOR takođe osjeća nivoe ćelijskih hranljivih materija, kisika i energije.[13] mTOR-ski put je centralni regulator metabolizma i fiziologije sisara, s važnom ulogom u funkciji tkiva, uključujući jetru, mišiće, bijelo i smeđe masno tkivo,[14] i mozak; disreguliran je kod ljudskih bolesti, kao što su dijabetes, gojaznost, depresija i određeni karcinomi.[15][16] Rapamicin inhibira mTOR povezujući se sa njegovim unutarčelijskim receptorom FKBP12.[17][18] Kompleks FKBP12–rapamicin vezuje se direktno za FKBP12-rapamicinvezujući (FRB) domen mTOR, inhibirajući njegovu aktivnost.[18]

Kompleksi

[uredi | uredi izvor]

mTOR je katalitska podjedinica dva strukturno različita kompleksa: mTORC1 i mTORC2.[19] The two complexes localize to different subcellular compartments, thus affecting their activation and function.[20] Nakon aktivacije Rheb-om, mTORC1 se lokalizira na Ragulator-Rag kompleks na površini lizosoma gdje tada postaje aktivan, u prisustvu dovoljno aminokiselina.[21][22]

Klinički značaj

[uredi | uredi izvor]Starenje

[uredi | uredi izvor]

Utvrđeno je da smanjena aktivnost TOR produžava životni vijek u S. cerevisiae, C. elegans, i D. melanogaster.[23][24][25][26] Potvrđeno je da mTOR-ov inhibitor, rapamicin produžava životni vijek miševa.[27][28][29][30][31]

Pretpostavlja se da neki režimi ishrane, kao što su ograničenje kalorija i ograničenje metionina, uzrokuju produženje životnog vijeka, smanjenjem mTOR-ske aktivnosti.[23][24] Neke studije sugerirale su da se signalizacija mTOR-a može povećati tokom starenja, barem u specifičnim tkivima kao što je masno tkivo, a rapamicin može djelovati, djelimično blokirajući ovo povećanje.[32] Alternativna teorija je da je mTOR signalizacija primjer antagonističke plejotropije, a dok je visoka signalizacija mTOR dobra tokom ranog života, održava se na neprikladno visokom nivou u starosti. Restrikcija kalorija i restrikcija metionina mogu djelomično djelovati ograničavanjem nivoa esencijalnih aminokiselina, uključujući leucin i metionin, koji su snažni aktivatori mTOR-a.[33] Pokazalo se da davanje leucina u mozak pacova smanjuje unos hrane i tjelesnu težinu putem aktivacije mTOR puta u hipotalamusu.[34]

Kancer

[uredi | uredi izvor]Prekomjerna aktivacija signalizacije mTOR-a značajno doprinosi započinjanju i razvoju tumora, a otkriveno je da je aktivnost mTOR deregulirana kod mnogih tipova karcinoma uključujući karcinome dojke, pluća, prostate, melanoma, mjehura, mozga i bubrega.[35] Ima nekoliki razloga za konstitutivnu aktivaciju. Među najčešćim su mutacije tumor supresorskog gena PTEN. PTEN-ova fosfataza negativno utiče na signalizaciju mTOR, ometanjem efekta PI3K, uzvodnog efektora mTOR. Osim toga, aktivnost mTOR je deregulirana kod mnogih karcinoma, kao posljedica povećane aktivnosti PI3K ili Akt.[36] Slično tome, prekomjerna ekspresija nizvodnih mTOR efektora 4E-BP1, S6K i eIF4E dovodi do loše prognoze raka.[37] Također, mutacije TSC proteina koje inhibiraju aktivnost mTOR-a mogu dovesti do stanja pod nazivom kompleksne gomoljasate skleroze, koje se ispoljava kao benigne lezije i povećava rizik od karcinomskih ćelija bubrežne skleroze.[38]

Pokazalo se da povećanje aktivnosti mTOR-a pokreće progresiju ćelijskog ciklusa i povećava ćelijsku proliferaciju uglavnom zbog njegovog efekta na sintezu proteina. Štaviše, aktivni mTOR podržava rast tumora takođe indirektno inhibirajući autofagiju.[39] Konstitutivno aktivirani mTOR funkcionira u opskrbi karcinomskih ćelija kisikom i hranjivim tvarima, povećanjem translacije HIF1A i podržavanjem angiogeneze.[40] mTOR također pomaže u još jednoj metaboličkoj adaptaciji kancerogenih ćelija, kako bi podržao njihovu povećanu stopu rasta – aktivaciju glikolitskog metabolizma. Akt2, supstrat mTOR-a, posebno mTORC2, pojačava ekspresiju glikolitskog enzima PKM2 doprinoseći tako Warburgovom efektu.[41]

Poremećaji centralnog nervnog sistema / Funkcija mozga

[uredi | uredi izvor]Autizam

[uredi | uredi izvor]mTOR je umiješan u neuspjeh mehanizma 'orezivanja' ekscitatornih sinapsi kod poremećaja iz autističkog spektra.[42]

Alzheimerova bolest

[uredi | uredi izvor]mTOR signalizacija se ukršta sa nekoliko aspekata patoloških prfomjena kod Alzhemerovw bolesti (AD), sugerirajući njegovu potencijalnu ulogu kao doprinosa progresiji bolesti. Općenito, nalazi pokazuju hiperaktivnost signalizacije mTORa u mozgu sa AD. Naprimjer, postmortem studije ljudskog mozga sa AD otkrivaju disregulaciju u PTEN, Akt, S6K i mTOR.[43][44][45] Signalizacija mTOR-a povezana je usko s prisustvom rastvorljivih beta (Aβ) i tau proteina, koji se agregiraju i formiraju dva obilježja bolesti, Aβ plakove i neurofibrilne čvorove.[46] In vitro studije pokazale su da je Aβ aktivator PI3K/AKT put, koji zauzvrat aktivira mTOR.[47] Osim toga, primjena Aβ na N2K ćelije povećava ekspresiju p70S6K, nizvodne mete mTOR-a, za koju se zna da ima veću ekspresiju u neuronima koji na kraju razvijaju neurofibrilske zaplete.[48][49] Ćelije jajnika kineskog hrčka transficirane 7PA2 porodičnom AD mutacijom također pokazuju povećanu aktivnost mTOR-a u odnosu na kontrole, a hiperaktivnost je blokirana pomoću inhibitora gama-sekretaze.[50][51] Ove in vitro studije ukazuju na to da povećanje koncentracije Aβ povećava signalizaciju mTOR-a; međutim, smatra se da značajno velike, citotoksične koncentracije Aβ smanjuju tu signalizaciju.[52]

U skladu sa podacima uočenim in vitro, pokazalo se da su aktivnost mTOR-a i aktivirani p70S6K značajno povećani u korteksu i hipokampusu životinjskih modela AD, u poređenju sa kontrolama.[51][53] Farmakološko ili genetičko uklanjanje Aβ u životinjskim modelima AD eliminira poremećaj normalne aktivnosti mTOR-a, ukazujući na direktnu uključenost Aβ u njegovu signalizaciju.[53] Osim toga, ubrizgavanjem Aβ oligomera u hipokampus normalnih miševa, uočena je hiperaktivnost mTOR-a.[53] Čini se da su kognitivna oštećenja karakteristična za AD posredovana fosforilacijom PRAS-40, koja se odvaja od mTOR-ovoj hiperaktivnosti i omogućava mTOR-sku hiperaktivnost kada je fosforiliran; inhibiranje fosforilacije PRAS-40 sprečava hiperaktivnost mTOR-a izazvanu putem Aβ.[53][54][55] S obzirom na ove nalaze, čini se da je signalni put mTOR-a jedan od mehanizama Aβ-indukovane toksičnosti u AD. .

Limfoproliferativne bolesti

[uredi | uredi izvor]Hiperaktivni putevi mTOR-a su identificirani kod određenih limfoproliferativnih bolesti, kao što su autoimunski limfoproliferativni sindrom (ALPS),[56] multicentrična Castlemanova bolest,[57] i posttransplantacijski limfoproliferativni poremećaj (PTLD).[58]

Sinteza proteina i rast ćelija

[uredi | uredi izvor]Aktivacija mTORC1 potrebna je za sintezu proteina mišićnih miofibrila i skeletnu hipertrofiju mišića kod ljudi. kao odgovor i na fizičke vježbe i uzimanje određenih aminokiselina ili njihovih derivata.[59][60] Trajna inaktivacija signalizacije mTORC1 u skeletnim mišićima olakšava gubitak mišićne mase i snage tokom gubljenja mišića u starosti, kaheksije raka i atrofije zbog fizičke neaktivnosti.[59][60][61] Čini se da aktivacija mTORC2 posreduje u izrastanj neurita u diferenciranoj neuro2a ćeliji miša.[62] Intermitentna aktivacija mTOR-a u prefrontalnim neuronima pomoću β-hidroksi β-metilbutirata inhibira kognitivni pad koji je povezan sa starenjem i povezan sa dendritskim orezivanjem kod životinja, što je fenomen koji se također primjećuje kod ljudi.[63]

Mnoge aminokiseline izvedene iz proteina hrane podstiču aktivaciju mTORC1 i povećavaju sintezu proteina signalizacijom putem Rag GTPaza.

Skraćenice i prikazi:| • PLD: fosfolipaza D

• PA: fosfatidna kiselina

• mTOR: mehanička meta rapamicina

• AMP: adenozin monofosfat

• ATP: adenozin trifosfat

• AMPK: AMP-aktivirana protein kinaza

• PGC-1α: peroksizomski proliferator aktiviran receptor gama koaktivator-1α

• S6K1: p70S6 kinaza

• 4EBP1: eukariotski faktor inicijacije translacije 4E- vezujući protein 1

• eIF4E: eukariotski faktor inicijacije translacije 4E

• RPS6: ribosomalni protein S6

• eEF2: eukariotski faktor elongacije 2

• RE: vježba otpora; EE: vježba izdržljivosti

• Mio: miofibrilski; Mito: mitohondrijel

• AA: aminokiseline

• HMB: β-hidroksi β-metilbuterna kiselina

• ↑ predstavlja activaciju

•

T-inhibicije

Sklerodermija

[uredi | uredi izvor]Skleroderma, također poznata kao sistemska skleroza, je hronična sistemska autoimunska bolest koju karakteriše otvrdnuće (sklero) kože (derma ) koje u težim oblicima zahvata unutrašnje organe.[65][66] mTOR ima ulogu u bolestima fibroza i autoimunosti, a blokada mTORC puta se istražuje kao tretman za sklerodermu.[8]

Bolest skladištenja glikogena

[uredi | uredi izvor]Neki članci navode da rapamicin može inhibirati mTORC1 tako da se fosforilacija GS (glikogen-sintaze) može povećati u skeletnim mišićima. Ovo otkriće predstavlja potencijalni novi terapijski pristup za bolest skladištenja glikogena koja uključuje akumulaciju glikogena u mišićima.

Anti-kancer

[uredi | uredi izvor]Postoje dva primarna nhibitoramTOR-a i koji se koriste u liječenju karcinoma kod ljudi, temsirolimus i everolimus. mTOR inhibitori su našli primenu u liječenju različitih malignosti, uključujući karcinom bubrežnih ćelija (temsirolimus) i rak gušterače, rak dojke i karcinom bubrežnih ćelija (everolimus).[67] Kompletan mehanizam ovih agenasa nije jasan, ali se smatra da funkcionišu tako što ometaju angiogenezu tumora i uzrokuju oštećenje G1/S tranzicije.[68]

Protiv starenja

[uredi | uredi izvor]Inhibitori mTOR-a mogu biti korisni za liječenje/prevenciju nekoliko stanja povezanih s godinama,[69] uključujući neurodegenerativne bolesti, kao što su Alzheimerova i Parkinsonova bolest.[70] Nakon kratkotrajnog tretmana inhibitorima mTORa, kao što su dactolisib i everolimus, kod starijih osoba (65 i više godina), liječeni su imali smanjen broj infekcija u toku jedne godine.[71]

Za razne prirodne spojeve, uključujući epigalokatehin-galat (EGCG), kofein, kurkumin, berberin, kvercetin, resveratrol i pterostilben, prijavljeno je da inhibiraju mTOR kada se primjenjuju na izolirane ćelije u kulturi.[72][73][74] Još uvijek ne postoje visokokvalitetni dokazi da ove tvari inhibiraju signalizaciju mTOR-a ili produžuju životni vijek kada ih ljudi uzimaju kao dodatke ishrani, uprkos ohrabrujućim rezultatima kod životinja kao što su vinske mušice i miševi. Razne prosudbe su u toku.[75][76]

Interakcije

[uredi | uredi izvor]Pokazalo se da mehancistička meta rapamicina reaguje sa:[77]

- ABL1,[78]

- AKT1,[79][80]

- IGF-IR,[11]

- InsR,[11]

- CLIP1,[81]

- EIF3F[82]

- EIF4EBP1,[83][84][85][86][87][88][89]

- FKBP1A,[12][90][91][92][93]

- GPHN,[94]

- KIAA1303,[83][84][85][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106]

- PRKCD,[107]

- PS6KB1,[84][86][87][88][102][105][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115]

- RHEB,[116][117][118]

- RICTOR,[97][103][105][106]

- STAT1,[119]

- STAT3,[120][121]

- TPCN1;

- TPCN2,[122] i

- UBQLN1.[123]

Reference

[uredi | uredi izvor]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000198793 - Ensembl, maj 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000028991 - Ensembl, maj 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Sabers CJ, Martin MM, Brunn GJ, Williams JM, Dumont FJ, Wiederrecht G, Abraham RT (Jan 1995). "Isolation of a Protein Target of the FKBP12-Rapamycin Complex in Mammalian Cells". J. Biol. Chem. 270 (2): 815–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.2.815. PMID 7822316.

- ^ Brown EJ, Albers MW, Shin TB, Ichikawa K, Keith CT, Lane WS, Schreiber SL (juni 1994). "A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex". Nature. 369 (6483): 756–8. Bibcode:1994Natur.369..756B. doi:10.1038/369756a0. PMID 8008069. S2CID 4359651.

- ^ Sabers CJ, Martin MM, Brunn GJ, Williams JM, Dumont FJ, Wiederrecht G, Abraham RT (januar 1995). "Isolation of a protein target of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex in mammalian cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (2): 815–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.2.815. PMID 7822316.

- ^ a b Mitra A, Luna JI, Marusina AI, Merleev A, Kundu-Raychaudhuri S, Fiorentino D, Raychaudhuri SP, Maverakis E (novembar 2015). "Dual mTOR Inhibition Is Required to Prevent TGF-β-Mediated Fibrosis: Implications for Scleroderma". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 135 (11): 2873–6. doi:10.1038/jid.2015.252. PMC 4640976. PMID 26134944.

- ^ a b c Lipton JO, Sahin M (oktobar 2014). "The neurology of mTOR". Neuron. 84 (2): 275–291. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.034. PMC 4223653. PMID 25374355.

The mTOR signaling pathway acts as a molecular systems integrator to support organismal and cellular interactions with the environment. The mTOR pathway regulates homeostasis by directly influencing protein synthesis, transcription, autophagy, metabolism, and organelle biogenesis and maintenance. It is not surprising then that mTOR signaling is implicated in the entire hierarchy of brain function including the proliferation of neural stem cells, the assembly and maintenance of circuits, experience-dependent plasticity and regulation of complex behaviors like feeding, sleep and circadian rhythms. ...

mTOR function is mediated through two large biochemical complexes defined by their respective protein composition and have been extensively reviewed elsewhere(Dibble and Manning, 2013; Laplante and Sabatini, 2012)(Figure 1B). In brief, common to both mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) are: mTOR itself, mammalian lethal with sec13 protein 8 (mLST8; also known as GβL), and the inhibitory DEP domain containing mTOR-interacting protein (DEPTOR). Specific to mTORC1 is the regulator-associated protein of the mammalian target of rapamycin (Raptor) and proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa (PRAS40)(Kim et al., 2002; Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). Raptor is essential to mTORC1 activity. The mTORC2 complex includes the rapamycin insensitive companion of mTOR (Rictor), mammalian stress activated MAP kinase-interacting protein 1 (mSIN1), and proteins observed with rictor 1 and 2 (PROTOR 1 and 2)(Jacinto et al., 2006; Jacinto et al., 2004; Pearce et al., 2007; Sarbassov et al., 2004)(Figure 1B). Rictor and mSIN1 are both critical to mTORC2 function.

Figure 1: Domain structure of the mTOR kinase and components of mTORC1 and mTORC2

Figure 2: The mTOR Signaling Pathway - ^ a b Hay N, Sonenberg N (august 2004). "Upstream and downstream of mTOR". Genes & Development. 18 (16): 1926–45. doi:10.1101/gad.1212704. PMID 15314020.

- ^ a b c d Yin Y, Hua H, Li M, Liu S, Kong Q, Shao T, Wang J, Luo Y, Wang Q, Luo T, Jiang Y (januar 2016). "mTORC2 promotes type I insulin-like growth factor receptor and insulin receptor activation through the tyrosine kinase activity of mTOR". Cell Research. 26 (1): 46–65. doi:10.1038/cr.2015.133. PMC 4816127. PMID 26584640.

- ^ a b Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A, Lin S, Rüegg MA, Hall A, Hall MN (novembar 2004). "Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive". Nature Cell Biology. 6 (11): 1122–8. doi:10.1038/ncb1183. PMID 15467718. S2CID 13831153.

- ^ Tokunaga C, Yoshino K, Yonezawa K (januar 2004). "mTOR integrates amino acid- and energy-sensing pathways". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 313 (2): 443–6. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.07.019. PMID 14684182.

- ^ Wipperman MF, Montrose DC, Gotto AM, Hajjar DP (2019). "Mammalian Target of Rapamycin: A Metabolic Rheostat for Regulating Adipose Tissue Function and Cardiovascular Health". The American Journal of Pathology. 189 (3): 492–501. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.11.013. PMC 6412382. PMID 30803496.

- ^ Beevers CS, Li F, Liu L, Huang S (august 2006). "Curcumin inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin-mediated signaling pathways in cancer cells". International Journal of Cancer. 119 (4): 757–64. doi:10.1002/ijc.21932. PMID 16550606. S2CID 25454463.

- ^ Kennedy BK, Lamming DW (juni 2016). "The Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin: The Grand ConducTOR of Metabolism and Aging". Cell Metabolism. 23 (6): 990–1003. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.009. PMC 4910876. PMID 27304501.

- ^ Huang S, Houghton PJ (decembar 2001). "Mechanisms of resistance to rapamycins". Drug Resistance Updates. 4 (6): 378–91. doi:10.1054/drup.2002.0227. PMID 12030785.

- ^ a b Huang S, Bjornsti MA, Houghton PJ (2003). "Rapamycins: mechanism of action and cellular resistance". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2 (3): 222–32. doi:10.4161/cbt.2.3.360. PMID 12878853.

- ^ Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN (februar 2006). "TOR signaling in growth and metabolism". Cell. 124 (3): 471–84. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. PMID 16469695.

- ^ Betz C, Hall MN (novembar 2013). "Where is mTOR and what is it doing there?". The Journal of Cell Biology. 203 (4): 563–74. doi:10.1083/jcb.201306041. PMC 3840941. PMID 24385483.

- ^ Groenewoud MJ, Zwartkruis FJ (august 2013). "Rheb and Rags come together at the lysosome to activate mTORC1". Biochemical Society Transactions. 41 (4): 951–5. doi:10.1042/bst20130037. PMID 23863162. S2CID 8237502.

- ^ Efeyan A, Zoncu R, Sabatini DM (septembar 2012). "Amino acids and mTORC1: from lysosomes to disease". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 18 (9): 524–33. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2012.05.007. PMC 3432651. PMID 22749019.

- ^ a b Powers RW, Kaeberlein M, Caldwell SD, Kennedy BK, Fields S (januar 2006). "Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling". Genes & Development. 20 (2): 174–84. doi:10.1101/gad.1381406. PMC 1356109. PMID 16418483.

- ^ a b Kaeberlein M, Powers RW, Steffen KK, Westman EA, Hu D, Dang N, Kerr EO, Kirkland KT, Fields S, Kennedy BK (novembar 2005). "Regulation of yeast replicative life span by TOR and Sch9 in response to nutrients". Science. 310 (5751): 1193–6. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1193K. doi:10.1126/science.1115535. PMID 16293764. S2CID 42188272.

- ^ Jia K, Chen D, Riddle DL (august 2004). "The TOR pathway interacts with the insulin signaling pathway to regulate C. elegans larval development, metabolism and life span". Development. 131 (16): 3897–906. doi:10.1242/dev.01255. PMID 15253933.

- ^ Kapahi P, Zid BM, Harper T, Koslover D, Sapin V, Benzer S (maj 2004). "Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway". Current Biology. 14 (10): 885–90. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059. PMC 2754830. PMID 15186745.

- ^ Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, Nadon NL, Wilkinson JE, Frenkel K, Carter CS, Pahor M, Javors MA, Fernandez E, Miller RA (juli 2009). "Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice". Nature. 460 (7253): 392–5. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..392H. doi:10.1038/nature08221. PMC 2786175. PMID 19587680.

- ^ Miller RA, Harrison DE, Astle CM, Fernandez E, Flurkey K, Han M, Javors MA, Li X, Nadon NL, Nelson JF, Pletcher S, Salmon AB, Sharp ZD, Van Roekel S, Winkleman L, Strong R (juni 2014). "Rapamycin-mediated lifespan increase in mice is dose and sex dependent and metabolically distinct from dietary restriction". Aging Cell. 13 (3): 468–77. doi:10.1111/acel.12194. PMC 4032600. PMID 24341993.

- ^ Fok WC, Chen Y, Bokov A, Zhang Y, Salmon AB, Diaz V, Javors M, Wood WH, Zhang Y, Becker KG, Pérez VI, Richardson A (1. 1. 2014). "Mice fed rapamycin have an increase in lifespan associated with major changes in the liver transcriptome". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e83988. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...983988F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083988. PMC 3883653. PMID 24409289.

- ^ Arriola Apelo SI, Pumper CP, Baar EL, Cummings NE, Lamming DW (juli 2016). "Intermittent Administration of Rapamycin Extends the Life Span of Female C57BL/6J Mice". The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 71 (7): 876–81. doi:10.1093/gerona/glw064. PMC 4906329. PMID 27091134.

- ^ Popovich IG, Anisimov VN, Zabezhinski MA, Semenchenko AV, Tyndyk ML, Yurova MN, Blagosklonny MV (maj 2014). "Lifespan extension and cancer prevention in HER-2/neu transgenic mice treated with low intermittent doses of rapamycin". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 15 (5): 586–92. doi:10.4161/cbt.28164. PMC 4026081. PMID 24556924.

- ^ Baar EL, Carbajal KA, Ong IM, Lamming DW (februar 2016). "Sex- and tissue-specific changes in mTOR signaling with age in C57BL/6J mice". Aging Cell. 15 (1): 155–66. doi:10.1111/acel.12425. PMC 4717274. PMID 26695882.

- ^ Caron A, Richard D, Laplante M (Jul 2015). "The Roles of mTOR Complexes in Lipid Metabolism". Annual Review of Nutrition. 35: 321–48. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071714-034355. PMID 26185979.

- ^ Cota D, Proulx K, Smith KA, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Woods SC, Seeley RJ (maj 2006). "Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake". Science. 312 (5775): 927–30. Bibcode:2006Sci...312..927C. doi:10.1126/science.1124147. PMID 16690869. S2CID 6526786.

- ^ Xu K, Liu P, Wei W (decembar 2014). "mTOR signaling in tumorigenesis". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 1846 (2): 638–54. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.10.007. PMC 4261029. PMID 25450580.

- ^ Guertin DA, Sabatini DM (august 2005). "An expanding role for mTOR in cancer". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 11 (8): 353–61. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2005.06.007. PMID 16002336.

- ^ Pópulo H, Lopes JM, Soares P (2012). "The mTOR signalling pathway in human cancer". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 13 (2): 1886–918. doi:10.3390/ijms13021886. PMC 3291999. PMID 22408430.

- ^ Easton JB, Houghton PJ (oktobar 2006). "mTOR and cancer therapy". Oncogene. 25 (48): 6436–46. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209886. PMID 17041628.

- ^ Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM (januar 2011). "mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 12 (1): 21–35. doi:10.1038/nrm3025. PMC 3390257. PMID 21157483.

- ^ Thomas GV, Tran C, Mellinghoff IK, Welsbie DS, Chan E, Fueger B, Czernin J, Sawyers CL (januar 2006). "Hypoxia-inducible factor determines sensitivity to inhibitors of mTOR in kidney cancer". Nature Medicine. 12 (1): 122–7. doi:10.1038/nm1337. PMID 16341243. S2CID 1853822.

- ^ Nemazanyy I, Espeillac C, Pende M, Panasyuk G (august 2013). "Role of PI3K, mTOR and Akt2 signalling in hepatic tumorigenesis via the control of PKM2 expression". Biochemical Society Transactions. 41 (4): 917–22. doi:10.1042/BST20130034. PMID 23863156.

- ^ Tang G, Gudsnuk K, Kuo SH, Cotrina ML, Rosoklija G, Sosunov A, Sonders MS, Kanter E, Castagna C, Yamamoto A, Yue Z, Arancio O, Peterson BS, Champagne F, Dwork AJ, Goldman J, Sulzer D (septembar 2014). "Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits". Neuron. 83 (5): 1131–43. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.040. PMC 4159743. PMID 25155956.

- ^ Rosner M, Hanneder M, Siegel N, Valli A, Fuchs C, Hengstschläger M (juni 2008). "The mTOR pathway and its role in human genetic diseases". Mutation Research. 659 (3): 284–92. doi:10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.06.001. PMID 18598780.

- ^ Li X, Alafuzoff I, Soininen H, Winblad B, Pei JJ (august 2005). "Levels of mTOR and its downstream targets 4E-BP1, eEF2, and eEF2 kinase in relationships with tau in Alzheimer's disease brain". The FEBS Journal. 272 (16): 4211–20. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04833.x. PMID 16098202. S2CID 43085490.

- ^ Chano T, Okabe H, Hulette CM (septembar 2007). "RB1CC1 insufficiency causes neuronal atrophy through mTOR signaling alteration and involved in the pathology of Alzheimer's diseases". Brain Research. 1168 (1168): 97–105. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.075. PMID 17706618. S2CID 54255848.

- ^ Selkoe DJ (septembar 2008). "Soluble oligomers of the amyloid beta-protein impair synaptic plasticity and behavior". Behavioural Brain Research. 192 (1): 106–13. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.016. PMC 2601528. PMID 18359102.

- ^ Oddo S (januar 2012). "The role of mTOR signaling in Alzheimer disease". Frontiers in Bioscience. 4 (1): 941–52. doi:10.2741/s310. PMC 4111148. PMID 22202101.

- ^ An WL, Cowburn RF, Li L, Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Iqbal K, Iqbal IG, Winblad B, Pei JJ (august 2003). "Up-regulation of phosphorylated/activated p70 S6 kinase and its relationship to neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease". The American Journal of Pathology. 163 (2): 591–607. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63687-5. PMC 1868198. PMID 12875979.

- ^ Zhang F, Beharry ZM, Harris TE, Lilly MB, Smith CD, Mahajan S, Kraft AS (maj 2009). "PIM1 protein kinase regulates PRAS40 phosphorylation and mTOR activity in FDCP1 cells". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 8 (9): 846–53. doi:10.4161/cbt.8.9.8210. PMID 19276681.

- ^ Koo EH, Squazzo SL (juli 1994). "Evidence that production and release of amyloid beta-protein involves the endocytic pathway". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 269 (26): 17386–9. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)32449-3. PMID 8021238.

- ^ a b Caccamo A, Majumder S, Richardson A, Strong R, Oddo S (april 2010). "Molecular interplay between mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), amyloid-beta, and Tau: effects on cognitive impairments". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (17): 13107–20. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.100420. PMC 2857107. PMID 20178983.

- ^ Lafay-Chebassier C, Paccalin M, Page G, Barc-Pain S, Perault-Pochat MC, Gil R, Pradier L, Hugon J (juli 2005). "mTOR/p70S6k signalling alteration by Abeta exposure as well as in APP-PS1 transgenic models and in patients with Alzheimer's disease". Journal of Neurochemistry. 94 (1): 215–25. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03187.x. PMID 15953364. S2CID 8464608.

- ^ a b c d Caccamo A, Maldonado MA, Majumder S, Medina DX, Holbein W, Magrí A, Oddo S (mart 2011). "Naturally secreted amyloid-beta increases mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity via a PRAS40-mediated mechanism". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (11): 8924–32. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.180638. PMC 3058958. PMID 21266573.

- ^ Sancak Y, Thoreen CC, Peterson TR, Lindquist RA, Kang SA, Spooner E, Carr SA, Sabatini DM (mart 2007). "PRAS40 is an insulin-regulated inhibitor of the mTORC1 protein kinase". Molecular Cell. 25 (6): 903–15. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.003. PMID 17386266.

- ^ Wang L, Harris TE, Roth RA, Lawrence JC (juli 2007). "PRAS40 regulates mTORC1 kinase activity by functioning as a direct inhibitor of substrate binding". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (27): 20036–44. doi:10.1074/jbc.M702376200. PMID 17510057.

- ^ Völkl, Simon, et al. "Hyperactive mTOR pathway promotes lymphoproliferation and abnormal differentiation in autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome." Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 128.2 (2016): 227-238. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-11-685024

- ^ Arenas, Daniel J., et al. "Increased mTOR activation in idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease." Blood 135.19 (2020): 1673-1684. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019002792

- ^ El-Salem, Mouna, et al. "Constitutive activation of mTOR signaling pathway in post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders." Laboratory Investigation 87.1 (2007): 29-39. https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3700494

- ^ a b c Brook MS, Wilkinson DJ, Phillips BE, Perez-Schindler J, Philp A, Smith K, Atherton PJ (januar 2016). "Skeletal muscle homeostasis and plasticity in youth and ageing: impact of nutrition and exercise". Acta Physiologica. 216 (1): 15–41. doi:10.1111/apha.12532. PMC 4843955. PMID 26010896.

- ^ a b Brioche T, Pagano AF, Py G, Chopard A (april 2016). "Muscle wasting and aging: Experimental models, fatty infiltrations, and prevention" (PDF). Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 50: 56–87. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2016.04.006. PMID 27106402.

- ^ Drummond MJ, Dreyer HC, Fry CS, Glynn EL, Rasmussen BB (april 2009). "Nutritional and contractile regulation of human skeletal muscle protein synthesis and mTORC1 signaling". Journal of Applied Physiology. 106 (4): 1374–84. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.91397.2008. PMC 2698645. PMID 19150856.

- ^ Salto R, Vílchez JD, Girón MD, Cabrera E, Campos N, Manzano M, Rueda R, López-Pedrosa JM (2015). "β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate (HMB) Promotes Neurite Outgrowth in Neuro2a Cells". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0135614. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1035614S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135614. PMC 4534402. PMID 26267903.

- ^ Kougias DG, Nolan SO, Koss WA, Kim T, Hankosky ER, Gulley JM, Juraska JM (april 2016). "Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate ameliorates aging effects in the dendritic tree of pyramidal neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex of both male and female rats". Neurobiology of Aging. 40: 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.01.004. PMID 26973106. S2CID 3953100.

- ^ Phillips SM (maj 2014). "A brief review of critical processes in exercise-induced muscular hypertrophy". Sports Med. 44 Suppl 1: S71–S77. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0152-3. PMC 4008813. PMID 24791918.

- ^ Jimenez SA, Cronin PM, Koenig AS, O'Brien MS, Castro SV (15. 2. 2012). Varga J, Talavera F, Goldberg E, Mechaber AJ, Diamond HS (ured.). "Scleroderma". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Pristupljeno 5. 3. 2014.

- ^ Hajj-ali RA (juni 2013). "Systemic Sclerosis". Merck Manual Professional. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Pristupljeno 5. 3. 2014.

- ^ "Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors in solid tumours". Pharmaceutical Journal (jezik: engleski). Pristupljeno 18. 10. 2018.

- ^ Faivre S, Kroemer G, Raymond E (august 2006). "Current development of mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery (jezik: engleski). 5 (8): 671–88. doi:10.1038/nrd2062. PMID 16883305. S2CID 27952376.

- ^ Hasty P (februar 2010). "Rapamycin: the cure for all that ails". Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. 2 (1): 17–9. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjp033. PMID 19805415.

- ^ Bové J, Martínez-Vicente M, Vila M (august 2011). "Fighting neurodegeneration with rapamycin: mechanistic insights". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 12 (8): 437–52. doi:10.1038/nrn3068. PMID 21772323. S2CID 205506774.

- ^ Mannick JB, Morris M, Hockey HP, Roma G, Beibel M, Kulmatycki K, Watkins M, Shavlakadze T, Zhou W, Quinn D, Glass DJ, Klickstein LB (juli 2018). "TORC1 inhibition enhances immune function and reduces infections in the elderly". Science Translational Medicine. 10 (449): eaaq1564. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaq1564. PMID 29997249.

- ^ Estrela JM, Ortega A, Mena S, Rodriguez ML, Asensi M (2013). "Pterostilbene: Biomedical applications". Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 50 (3): 65–78. doi:10.3109/10408363.2013.805182. PMID 23808710. S2CID 45618964.

- ^ McCubrey JA, Lertpiriyapong K, Steelman LS, Abrams SL, Yang LV, Murata RM, et al. (juni 2017). "Effects of resveratrol, curcumin, berberine and other nutraceuticals on aging, cancer development, cancer stem cells and microRNAs". Aging. 9 (6): 1477–1536. doi:10.18632/aging.101250. PMC 5509453. PMID 28611316.

- ^ Malavolta M, Bracci M, Santarelli L, Sayeed MA, Pierpaoli E, Giacconi R, et al. (2018). "Inducers of Senescence, Toxic Compounds, and Senolytics: The Multiple Faces of Nrf2-Activating Phytochemicals in Cancer Adjuvant Therapy". Mediators of Inflammation. 2018: 4159013. doi:10.1155/2018/4159013. PMC 5829354. PMID 29618945.

- ^ Gómez-Linton DR, Alavez S, Alarcón-Aguilar A, López-Diazguerrero NE, Konigsberg M, Pérez-Flores LJ (oktobar 2019). "Some naturally occurring compounds that increase longevity and stress resistance in model organisms of aging". Biogerontology. 20 (5): 583–603. doi:10.1007/s10522-019-09817-2. PMID 31187283. S2CID 184483900.

- ^ Li W, Qin L, Feng R, Hu G, Sun H, He Y, Zhang R (juli 2019). "Emerging senolytic agents derived from natural products". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 181: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2019.05.001. PMID 31077707. S2CID 147704626.

- ^ "mTOR protein interactors". Human Protein Reference Database. Johns Hopkins University and the Institute of Bioinformatics. Arhivirano s originala, 28. 6. 2015. Pristupljeno 6. 12. 2010.

- ^ Kumar V, Sabatini D, Pandey P, Gingras AC, Majumder PK, Kumar M, Yuan ZM, Carmichael G, Weichselbaum R, Sonenberg N, Kufe D, Kharbanda S (april 2000). "Regulation of the rapamycin and FKBP-target 1/mammalian target of rapamycin and cap-dependent initiation of translation by the c-Abl protein-tyrosine kinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (15): 10779–87. doi:10.1074/jbc.275.15.10779. PMID 10753870.

- ^ Sekulić A, Hudson CC, Homme JL, Yin P, Otterness DM, Karnitz LM, Abraham RT (juli 2000). "A direct linkage between the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-AKT signaling pathway and the mammalian target of rapamycin in mitogen-stimulated and transformed cells". Cancer Research. 60 (13): 3504–13. PMID 10910062.

- ^ Cheng SW, Fryer LG, Carling D, Shepherd PR (april 2004). "Thr2446 is a novel mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) phosphorylation site regulated by nutrient status". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (16): 15719–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.C300534200. PMID 14970221.

- ^ Choi JH, Bertram PG, Drenan R, Carvalho J, Zhou HH, Zheng XF (oktobar 2002). "The FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein (FRAP) is a CLIP-170 kinase". EMBO Reports. 3 (10): 988–94. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvf197. PMC 1307618. PMID 12231510.

- ^ Harris TE, Chi A, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Rhoads RE, Lawrence JC (april 2006). "mTOR-dependent stimulation of the association of eIF4G and eIF3 by insulin". The EMBO Journal. 25 (8): 1659–68. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601047. PMC 1440840. PMID 16541103.

- ^ a b Schalm SS, Fingar DC, Sabatini DM, Blenis J (maj 2003). "TOS motif-mediated raptor binding regulates 4E-BP1 multisite phosphorylation and function". Current Biology. 13 (10): 797–806. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00329-4. PMID 12747827.

- ^ a b c Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, Yoshino K, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Avruch J, Yonezawa K (juli 2002). "Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action". Cell. 110 (2): 177–89. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00833-4. PMID 12150926.

- ^ a b Wang L, Rhodes CJ, Lawrence JC (august 2006). "Activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) by insulin is associated with stimulation of 4EBP1 binding to dimeric mTOR complex 1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (34): 24293–303. doi:10.1074/jbc.M603566200. PMID 16798736.

- ^ a b Long X, Lin Y, Ortiz-Vega S, Yonezawa K, Avruch J (april 2005). "Rheb binds and regulates the mTOR kinase". Current Biology. 15 (8): 702–13. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.053. PMID 15854902.

- ^ a b Takahashi T, Hara K, Inoue H, Kawa Y, Tokunaga C, Hidayat S, Yoshino K, Kuroda Y, Yonezawa K (septembar 2000). "Carboxyl-terminal region conserved among phosphoinositide-kinase-related kinases is indispensable for mTOR function in vivo and in vitro". Genes to Cells. 5 (9): 765–75. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00365.x. PMID 10971657.

- ^ a b Burnett PE, Barrow RK, Cohen NA, Snyder SH, Sabatini DM (februar 1998). "RAFT1 phosphorylation of the translational regulators p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (4): 1432–7. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.1432B. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.4.1432. PMC 19032. PMID 9465032.

- ^ Wang X, Beugnet A, Murakami M, Yamanaka S, Proud CG (april 2005). "Distinct signaling events downstream of mTOR cooperate to mediate the effects of amino acids and insulin on initiation factor 4E-binding proteins". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (7): 2558–72. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.7.2558-2572.2005. PMC 1061630. PMID 15767663.

- ^ Choi J, Chen J, Schreiber SL, Clardy J (juli 1996). "Structure of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex interacting with the binding domain of human FRAP". Science. 273 (5272): 239–42. Bibcode:1996Sci...273..239C. doi:10.1126/science.273.5272.239. PMID 8662507. S2CID 27706675.

- ^ Luker KE, Smith MC, Luker GD, Gammon ST, Piwnica-Worms H, Piwnica-Worms D (august 2004). "Kinetics of regulated protein-protein interactions revealed with firefly luciferase complementation imaging in cells and living animals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (33): 12288–93. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10112288L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0404041101. PMC 514471. PMID 15284440.

- ^ Banaszynski LA, Liu CW, Wandless TJ (april 2005). "Characterization of the FKBP.rapamycin.FRB ternary complex". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (13): 4715–21. doi:10.1021/ja043277y. PMID 15796538.

- ^ Sabers CJ, Martin MM, Brunn GJ, Williams JM, Dumont FJ, Wiederrecht G, Abraham RT (januar 1995). "Isolation of a protein target of the FKBP12-rapamycin complex in mammalian cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (2): 815–22. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.2.815. PMID 7822316.

- ^ Sabatini DM, Barrow RK, Blackshaw S, Burnett PE, Lai MM, Field ME, Bahr BA, Kirsch J, Betz H, Snyder SH (maj 1999). "Interaction of RAFT1 with gephyrin required for rapamycin-sensitive signaling". Science. 284 (5417): 1161–4. Bibcode:1999Sci...284.1161S. doi:10.1126/science.284.5417.1161. PMID 10325225.

- ^ Ha SH, Kim DH, Kim IS, Kim JH, Lee MN, Lee HJ, Kim JH, Jang SK, Suh PG, Ryu SH (decembar 2006). "PLD2 forms a functional complex with mTOR/raptor to transduce mitogenic signals". Cellular Signalling. 18 (12): 2283–91. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.021. PMID 16837165.

- ^ Buerger C, DeVries B, Stambolic V (juni 2006). "Localization of Rheb to the endomembrane is critical for its signaling function". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 344 (3): 869–80. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.220. PMID 16631613.

- ^ a b Jacinto E, Facchinetti V, Liu D, Soto N, Wei S, Jung SY, Huang Q, Qin J, Su B (oktobar 2006). "SIN1/MIP1 maintains rictor-mTOR complex integrity and regulates Akt phosphorylation and substrate specificity". Cell. 127 (1): 125–37. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.033. PMID 16962653.

- ^ McMahon LP, Yue W, Santen RJ, Lawrence JC (januar 2005). "Farnesylthiosalicylic acid inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity both in cells and in vitro by promoting dissociation of the mTOR-raptor complex". Molecular Endocrinology. 19 (1): 175–83. doi:10.1210/me.2004-0305. PMID 15459249.

- ^ Oshiro N, Yoshino K, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Hara K, Eguchi S, Avruch J, Yonezawa K (april 2004). "Dissociation of raptor from mTOR is a mechanism of rapamycin-induced inhibition of mTOR function". Genes to Cells. 9 (4): 359–66. doi:10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00727.x. PMID 15066126.

- ^ Kawai S, Enzan H, Hayashi Y, Jin YL, Guo LM, Miyazaki E, Toi M, Kuroda N, Hiroi M, Saibara T, Nakayama H (juli 2003). "Vinculin: a novel marker for quiescent and activated hepatic stellate cells in human and rat livers". Virchows Archiv. 443 (1): 78–86. doi:10.1007/s00428-003-0804-4. PMID 12719976. S2CID 21552704.

- ^ Choi KM, McMahon LP, Lawrence JC (maj 2003). "Two motifs in the translational repressor PHAS-I required for efficient phosphorylation by mammalian target of rapamycin and for recognition by raptor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (22): 19667–73. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301142200. PMID 12665511.

- ^ a b Nojima H, Tokunaga C, Eguchi S, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Yoshino K, Hara K, Tanaka N, Avruch J, Yonezawa K (maj 2003). "The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) partner, raptor, binds the mTOR substrates p70 S6 kinase and 4E-BP1 through their TOR signaling (TOS) motif". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (18): 15461–4. doi:10.1074/jbc.C200665200. PMID 12604610.

- ^ a b Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, Markhard AL, Sabatini DM (april 2006). "Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB". Molecular Cell. 22 (2): 159–68. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. PMID 16603397.

- ^ Tzatsos A, Kandror KV (januar 2006). "Nutrients suppress phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling via raptor-dependent mTOR-mediated insulin receptor substrate 1 phosphorylation". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 26 (1): 63–76. doi:10.1128/MCB.26.1.63-76.2006. PMC 1317643. PMID 16354680.

- ^ a b c Sarbassov DD, Sabatini DM (novembar 2005). "Redox regulation of the nutrient-sensitive raptor-mTOR pathway and complex". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (47): 39505–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M506096200. PMID 16183647.

- ^ a b Yang Q, Inoki K, Ikenoue T, Guan KL (oktobar 2006). "Identification of Sin1 as an essential TORC2 component required for complex formation and kinase activity". Genes & Development. 20 (20): 2820–32. doi:10.1101/gad.1461206. PMC 1619946. PMID 17043309.

- ^ Kumar V, Pandey P, Sabatini D, Kumar M, Majumder PK, Bharti A, Carmichael G, Kufe D, Kharbanda S (mart 2000). "Functional interaction between RAFT1/FRAP/mTOR and protein kinase cdelta in the regulation of cap-dependent initiation of translation". The EMBO Journal. 19 (5): 1087–97. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.5.1087. PMC 305647. PMID 10698949.

- ^ Saitoh M, Pullen N, Brennan P, Cantrell D, Dennis PB, Thomas G (maj 2002). "Regulation of an activated S6 kinase 1 variant reveals a novel mammalian target of rapamycin phosphorylation site". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (22): 20104–12. doi:10.1074/jbc.M201745200. PMID 11914378.

- ^ Chiang GG, Abraham RT (juli 2005). "Phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) at Ser-2448 is mediated by p70S6 kinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (27): 25485–90. doi:10.1074/jbc.M501707200. PMID 15899889.

- ^ Holz MK, Blenis J (juli 2005). "Identification of S6 kinase 1 as a novel mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-phosphorylating kinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (28): 26089–93. doi:10.1074/jbc.M504045200. PMID 15905173.

- ^ Isotani S, Hara K, Tokunaga C, Inoue H, Avruch J, Yonezawa K (novembar 1999). "Immunopurified mammalian target of rapamycin phosphorylates and activates p70 S6 kinase alpha in vitro". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (48): 34493–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.48.34493. PMID 10567431.

- ^ Toral-Barza L, Zhang WG, Lamison C, Larocque J, Gibbons J, Yu K (juni 2005). "Characterization of the cloned full-length and a truncated human target of rapamycin: activity, specificity, and enzyme inhibition as studied by a high capacity assay". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 332 (1): 304–10. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.117. PMID 15896331.

- ^ Ali SM, Sabatini DM (maj 2005). "Structure of S6 kinase 1 determines whether raptor-mTOR or rictor-mTOR phosphorylates its hydrophobic motif site". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (20): 19445–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.C500125200. PMID 15809305.

- ^ Edinger AL, Linardic CM, Chiang GG, Thompson CB, Abraham RT (decembar 2003). "Differential effects of rapamycin on mammalian target of rapamycin signaling functions in mammalian cells". Cancer Research. 63 (23): 8451–60. PMID 14679009.

- ^ Leone M, Crowell KJ, Chen J, Jung D, Chiang GG, Sareth S, Abraham RT, Pellecchia M (august 2006). "The FRB domain of mTOR: NMR solution structure and inhibitor design". Biochemistry. 45 (34): 10294–302. doi:10.1021/bi060976+. PMID 16922504.

- ^ Long X, Ortiz-Vega S, Lin Y, Avruch J (juni 2005). "Rheb binding to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is regulated by amino acid sufficiency". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (25): 23433–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.C500169200. PMID 15878852.

- ^ Smith EM, Finn SG, Tee AR, Browne GJ, Proud CG (maj 2005). "The tuberous sclerosis protein TSC2 is not required for the regulation of the mammalian target of rapamycin by amino acids and certain cellular stresses". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (19): 18717–27. doi:10.1074/jbc.M414499200. PMID 15772076.

- ^ Bernardi R, Guernah I, Jin D, Grisendi S, Alimonti A, Teruya-Feldstein J, Cordon-Cardo C, Simon MC, Rafii S, Pandolfi PP (august 2006). "PML inhibits HIF-1alpha translation and neoangiogenesis through repression of mTOR". Nature. 442 (7104): 779–85. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..779B. doi:10.1038/nature05029. PMID 16915281. S2CID 4427427.

- ^ Kristof AS, Marks-Konczalik J, Billings E, Moss J (septembar 2003). "Stimulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT1)-dependent gene transcription by lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma is regulated by mammalian target of rapamycin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (36): 33637–44. doi:10.1074/jbc.M301053200. PMID 12807916.

- ^ Yokogami K, Wakisaka S, Avruch J, Reeves SA (januar 2000). "Serine phosphorylation and maximal activation of STAT3 during CNTF signaling is mediated by the rapamycin target mTOR". Current Biology. 10 (1): 47–50. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(99)00268-7. PMID 10660304.

- ^ Kusaba H, Ghosh P, Derin R, Buchholz M, Sasaki C, Madara K, Longo DL (januar 2005). "Interleukin-12-induced interferon-gamma production by human peripheral blood T cells is regulated by mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (2): 1037–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405204200. PMID 15522880.

- ^ Cang C, Zhou Y, Navarro B, Seo YJ, Aranda K, Shi L, Battaglia-Hsu S, Nissim I, Clapham DE, Ren D (februar 2013). "mTOR regulates lysosomal ATP-sensitive two-pore Na(+) channels to adapt to metabolic state". Cell. 152 (4): 778–90. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.023. PMC 3908667. PMID 23394946.

- ^ Wu S, Mikhailov A, Kallo-Hosein H, Hara K, Yonezawa K, Avruch J (januar 2002). "Characterization of ubiquilin 1, an mTOR-interacting protein". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1542 (1–3): 41–56. doi:10.1016/S0167-4889(01)00164-1. PMID 11853878.

Dopunska literatura

[uredi | uredi izvor]- Saxton RA, Sabatini DM (mart 2017). "mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease". Cell. 168 (6): 960–976. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004. PMC 5394987. PMID 28283069.

Vanjski linkovi

[uredi | uredi izvor]- mTOR protein na US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- "mTOR Signaling Pathway in Pathway Interaction Database". National Cancer Institute. Arhivirano s originala, 18. 3. 2013. Pristupljeno 18. 10. 2015.

- P42345